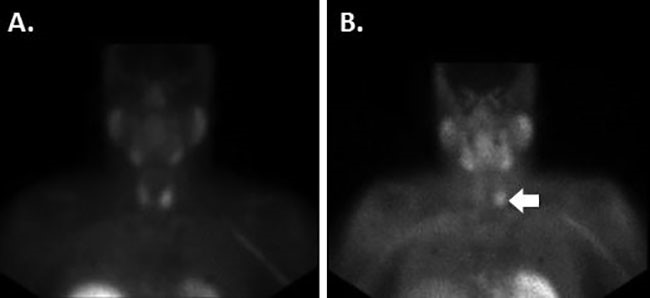

Figure 2. Infraumbilical hernia containing fat and a portion of the transverse colon

The patient was taken emergently to the operating room, where she underwent an exploratory laparotomy, enterolysis, partial transverse colectomy, and a transverse loop colostomy. On entering the abdominal cavity, multiple midline defects were noted, along with one defect that tracked from the midline to the left abdominal wall, anterior to the fascia. This lateral defect contained a loop of bowel that was necrotic on the anti-mesenteric aspect and viable on the mesenteric aspect, which was recognized to be a Richter hernia. The necrotic bowel was excised and a transverse loop colostomy was made. The patient tolerated the procedure well, had an uncomplicated postoperative course, and was discharged home on the fourth postoperative day.

Discussion

In 1558, Fabricius Hildanus reported the first case of Richter hernia; however, it was not until 1778 that German surgeon August Gottlieb Richter gave his scientific description of this rare entity that would later adopt his name.1 A Richter hernia occurs when the anti-mesenteric wall of the intestine protrudes, causing strangulation without obstruction.2 They are most commonly diagnosed in patients 60 to 80 years of age and comprise up to 10 percent of all strangulated hernias.2 These hernias can occur in prior incisions, but they are more commonly seen in small hernia rings large enough to trap a small portion of the bowel wall.3,4 The most common locations of presentation are femoral hernias (72 to 88 percent), followed by inguinal canal hernias (12 to 24 percent), and abdominal wall incisional hernias (4 to 25 percent).5 Because patients infrequently have obstructive symptoms, they tend to progress more rapidly to gangrene than is typically seen in other types of strangulated hernias. Repair is typically approached in the pre-peritoneal fashion, with a mandatory laparotomy and resection of bowel if gangrenous or perforated.

The silent nature of this hernia's presentation, and the fact that the patient continues to pass flatus and bowel movements, makes it particularly dangerous. By the time of presentation, there is typically ischemia of the affected bowel. Due to this ischemia, intestinal resection is mandatory. Not only is there morbidity and mortality due to the hernia, but there is also morbidity and mortality due to the bowel resection.

The necrotic bowel is not the only worrisome aspect of these hernias. There are also other complications, which have been described in the literature, including spontaneous fistulae from the affected bowel and necrotic skin.6,7,8,10,11 Fluri et al. described Richter hernia as a complication of a colonoscopy.7 Another report described a case where a Richter hernia was misidentified as a groin abscess and was only later discovered upon exploration after feculent material started to drain from the "abscess."11 These examples demonstrate that there is no typical presentation of these hernias; vigilance is mandatory to reduce mortality and morbidity.

Conclusion

A Richter hernia is a rare entity that has the potential for serious morbidity if not diagnosed in a timely fashion. Early detection and surgical treatment are paramount to improving outcomes. Providers and patients should also be educated on Richter hernia symptoms to decrease the time to presentation.

Lessons Learned

Due to the presentation of our case, we feel that it is important to counsel patients on incisional hernias after their first surgery. It is also important for physicians to be aware of all of the ways that these hernias may present in order to prevent operative delay.

Authors

Kartik Katragadda, MD

Department of Surgery

Mercy Catholic Medical Center

Darby, Pennsylvania

Lauren M. DeStefano, MD

Department of Surgery

Mercy Catholic Medical Center

Darby, Pennsylvania

Mohammad Farrukh Khan, MD

Department of Surgery

Mercy Catholic Medical Center

Darby, Pennsylvania

Correspondence

Dr. Kartik Katragadda

1500 Lansdowne Avenue

Darby, PA 19023

Phone: (760) 520-9774

Email: kartik.katragadda@mercyhealth.org

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Steinke W, Zellweger R. Richter Hernia and Sir Frederick Treves: An Original Clinical Experience, Review, and Historical Overview. Ann Surg. 2000;232(5):710-718.

- Skandalakis PN1 Zoras O, Skandalakis JE, Mirilas P. Richter hernia: surgical anatomy and technique of repair. Am Surg. 2006;72(2):20003-1348

- Boughy JC, Nottingham JM, Walls AC. Richter hernia in the laparoscopic era: four case reports and review of the literature. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13(1):55-8.

- Kadiron S, Sayfan J, Friedamn S, Orda R. Richter hernia: a surgical pitfall. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;182(1):60-2.

- Arkoulis N, Savanis G, Simatos G. Richters type strangulated femoral hernia containing caecum and appendix masquerading as a groin abscess. J Surg Case Rep. 2012(6):6. doi:10.1093/jscr/2012.6.6.

- Ahi KS, Moudgil A, Aggarwal K, Sharma C, Singh K. A rare case of spontaneous inguinal faecal fistula as a complication of incarcerated Richter hernia with brief review of literature. BMC Surg. 2015;15:67.

- Rao PL, Mitra SK, Pathak IC. Fecal fistula developing in inguinal hernia. Indian J Pediatr. 1980;47(3):253-255.

- Fluri P, Keller W, Nussbaumer P. Richters hernia after colonoscopy: a rare complication. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63(1):177-178.

- Sahsamanis G, Samaras S, Gkouzis K, Dimitrakopoulos G. Strangulated Richters incisional hernia presenting as an abdominal mass with necrosis of the overlapping skin. A case report and review of the literature. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5(3):253-256. doi:10.1002/ccr3.776.

- Power DA, Edward N, Catto GR, Muirhead N, Macleod A, Engeset J. Richters hernia: an unrecognised complication of chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. BMJ. 1981;283(6290):528-528. doi:10.1136/bmj.283.6290.528.

- Elenwo S, Igwe P, Jamabo R, Sonye U. Spontaneous entero-labial fistula complicating Richters hernia: Report of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;20:27-29. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.01.003.

- Kang CH, Tsai CY. Richter femoral hernia manifested by a progressive ileus. Formosan J Surg. 2014;47(5):193-196.