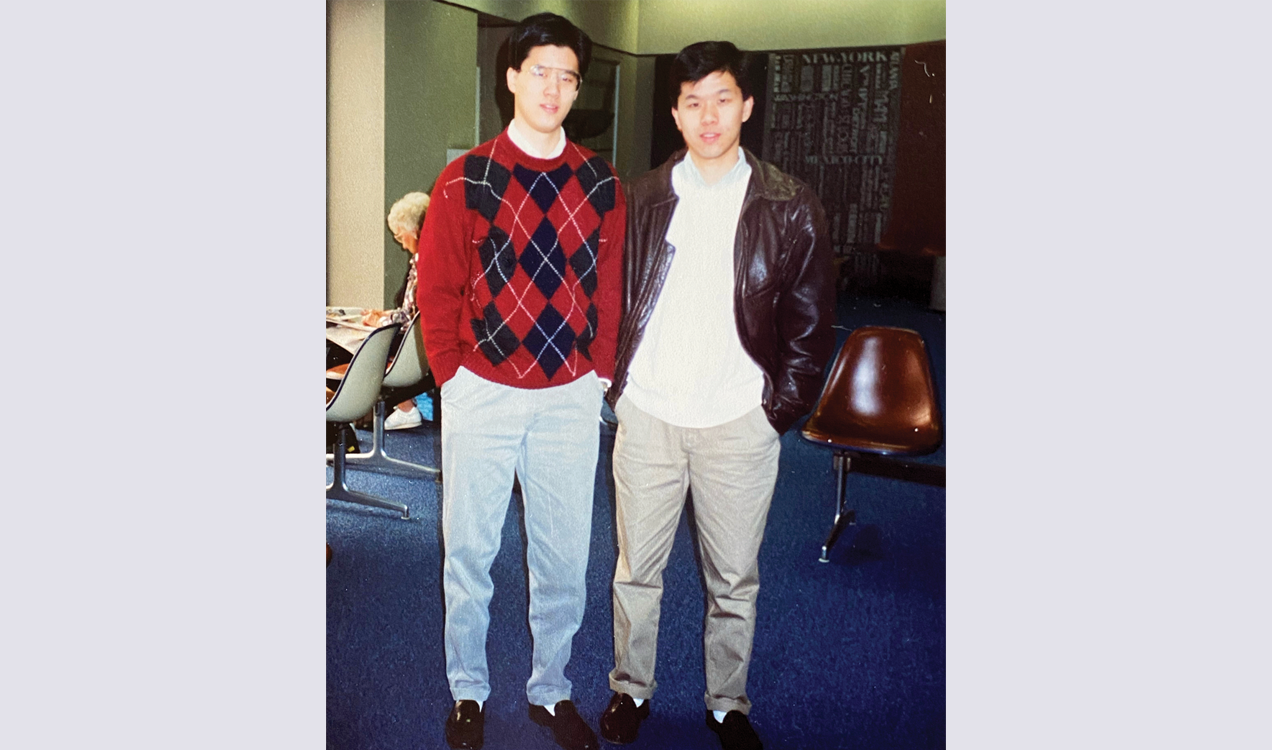

Drs. Erin Gillaspie and Devin Gillaspie

The “Gillaspie Girls”—as they are affectionately known—share the unique space occupied by a limited number of sibling-surgeon duos. But as women in the historically male-dominated field of surgery, their story is even more remarkable.

Erin A. Gillaspie, MD, MPH, FACS, assistant professor and head of thoracic surgery robotics in the Department of Thoracic Surgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, TN, and Devin B. Gillaspie, MD, assistant professor in the Division of Trauma and Critical Care Surgery at The University of Tennessee in Knoxville, described an “idyllic” childhood growing up in Mississauga in Ontario, Canada, with loving and nurturing parents.

Just about every day, the girls spent time playing outside, riding their purple bikes outfitted with streamers and visiting the local candy shop and bookstore. Their mom also regularly brought young Erin and Devin to the library where she would read them “beautiful books with women heroines” like Meg Murry from A Wrinkle in Time and Anne of Green Gables.

“When our mom went back to work, she purposely chose to work for women CEOs so that Devin and I grew up knowing that women could do anything. We could be anything,” said Dr. Erin Gillaspie.

The Gillaspie childhood also was “messy,” but in a good way, according to the sisters. With a dad who was a “sort of mad scientist and loved to build things,” the girls were encouraged to constantly ask questions and do crazy experiments. In fact, Erin bought her first microscope when she was in first grade, and her dad would help her make slides out of things they found in the backyard.

“We had such a wonderful, rich childhood—growing up in an environment where intelligence was prized and curiosity was encouraged, and we were loved unconditionally,” said Dr. Erin Gillaspie. “There was never a time when we doubted our ability to accomplish our goals or overcome a hurdle, which was brilliant.”

It was in those early years that Dr. Erin Gillaspie fell in love with the possibility of a career in surgery. While their grandfather was battling mesothelioma, she regularly saw the large scar on his side as they worked together in the garden. This is when her passion for medicine materialized.

“I remember seeing his scar and I’d ask, ‘Papa, why did they cut you in half?’ Unfortunately, just like cancer often does, it came back, and he didn’t have any more treatment options. Even at the end of his life, when he barely had any energy, he would pull me up onto his knee with all his might and share his Jell-O with me,” she said, adding that watching her Papa fight the disease “left an indelible mark” on her soul.

In her teen years, Dr. Erin Gillaspie’s fascination with the medical field continued. After the family moved from Canada to Florida, their mom took a job at a hospital. In order to spend more time with her, the sisters—who were just 13 and 11 years old at the time—started volunteering at the hospital. The girls were lucky enough to receive an offer from a surgeon that they could not refuse: Do you want to watch a surgery?

“Absolutely,” said Dr. Erin Gillaspie. “So, they put us in scrubs and told us if you’re going to pass out, hit the wall, not the patient. We had the biggest smiles on our faces. It was a total knee replacement with saws buzzing and bone fragments flying. We were enthralled. It was the most extraordinary thing.”

After that, young Erin asked permission to start regularly volunteering in the operating rooms, helping with room turnover, and in between, she’d get to watch surgeries. Eventually, she observed her first lung operation. “In that moment, I said, ‘This is what I’m going to do with my life. I’m going to be a lung surgeon so I can take care of people like my Papa and give little kids the gift of getting to know their grandparents,” she shared.

For Dr. Devin Gillaspie, the realization that surgery was her future was not as direct. With an interest in bacteria, she studied microbiology for her undergraduate degree and later worked in a bacterial pathogenesis and immunology laboratory. Dr. Devin Gillaspie loved it, so naturally she thought she was going to be an infectious disease doctor.

But during her surgery clerkship at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in FL, she worked with surgeons who were “great at teaching and involving the medical students.” Dr. Devin Gillaspie was a lucky beneficiary of some of these hands-on lessons. During one operation, she was given the opportunity to make an incision and open the abdomen.

“I said, ‘Oh, my gosh, this is really great.’ I was so amazed that as a med student, I was allowed to do that. But also, having my hands in an abdomen was such a cool experience. I called Erin and told her, ‘I’m going to do surgery instead,’” said Dr. Devin Gillaspie.

Both sisters agreed that they were fortunate from very early on—even before high school—to have wonderful mentors who were generous with invitations to learn alongside them in clinics and operating rooms. And from the “second we hit the doors of medical school, we had wonderful mentors at the resident and attending levels who just wanted us to love what they do as much as they did,” Dr. Erin Gillaspie said.

In her second year of fellowship at Vanderbilt University, Dr. Devin Gillaspie was able to work on some cases with her sister. There is one case—their first together—that she will never forget. When Dr. Devin Gillaspie learned that she would be performing a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) for a hemothorax, she called Dr. Erin Gillaspie, whose “happy place is the chest.” When the team suggested that they “call thoracic,” Dr. Devin Gillaspie said, “I’ve already done that and requested a particular surgeon to help me out.”

“When I told the patient that my sister—who is a cardiothoracic surgeon and specializes in cases like his—would be helping me out in the OR, he was so excited, especially after he learned that he was the first person we’d ever worked on together,” said Dr. Devin Gillaspie. “One of the trauma faculty members hustled down to the OR to make sure he captured a photo of us operating together. He said, ‘Here’s your photo for your parents.’”

Dr. Erin Gillaspie joked that even though the sisters are not twins, they should have been, and that came to light more than ever during this operation. “We have the same mannerisms, and we think the same way. We didn’t have to talk to each other because we just knew what the other person was thinking. We were extremely choreographed and in the zone.”

Although women remain significantly underrepresented in surgery, the sisters are passionately involved in helping to share the joy of their profession with medical students and residents.

“We have to attract women to surgery in an intentional and meaningful way,” Dr. Erin Gillaspie said. “We try to inspire as many people as possible to choose this wonderful field because we truly have the best job in the world. The future is so bright.”