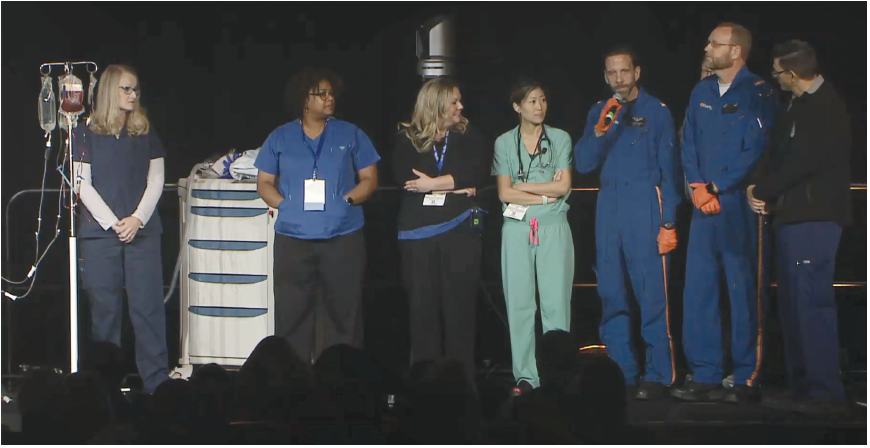

Surgeon receives care in system he created

Dr. Maxson shared his experience as both a surgeon and a patient with the Arkansas Trauma System—a system he helped to establish—in his keynote address.

Dr. Maxson was on call at Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Little Rock (where he is chief of the trauma program) on September 1, 2017. He was riding home on his Triumph Bonneville during a quick break when he was struck by another driver in a Jeep Cherokee. After the initial shock of the situation started to subside, Dr. Maxson asked a couple of helpful individuals to make two calls: one to 911 and the other to Children’s Hospital informing them he couldn’t take call that night.

Dr. Maxson requested that the paramedics take him to the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Hospital—the only ACS-verified adult Level I trauma center in the state.

“First and foremost, you should have the opportunity to be cared for at an ACS Level I trauma center, and unfortunately that is not the case everywhere, and so we are going to keep pushing until that becomes a reality. I’ve ridden the beautiful bike everywhere in the state of Arkansas, and it’s just a fact that had I not been that close to UAMS Hospital, the story would have turned out differently.”

The crash left Dr. Maxson with multiple injuries, including broken bones in his right arm, torn ligaments and a proximal tibial fracture, a torn bladder, and, what he called the “coup de grace,” a shattered pelvis.

Upon arriving at UAMS, Dr. Maxson said he was instantly identified by colleagues, some former students, whom he credits with saving his life. Dr. Maxson eventually underwent five operations in as many days.

“Do the things you do, do them right, and do them every time,” he said. “Do not veer from your protocol. Damage control resuscitation works. Hypotensive resuscitation works. Our adherence to protocols has to be baked-in. And what you do with the data enables us to create a clinical practice guideline because it takes the best information out there and lays it out, tracks it, and holds us responsible for that.”

After returning home a few weeks later, Dr. Maxson was able to resume his work remotely as Chair of the COT Verification Review Committee, as well as prepare for Arkansas Children’s Hospital’s upcoming verification visit. These activities were essential to his recovery, he said, as they kept him focused on goal-oriented tasks.

Dr. Maxson concluded his presentation by underscoring the importance of postdischarge care for trauma patients, including assistance obtaining rehabilitation equipment, scheduling appointments, and working with insurance companies.

“Patients need a navigator. I live in the system, and it was very difficult. The insurance claims process is purposely obfuscating. How do you handle it when you’re getting bills, and the insurance is saying they’re not going to pay for it? I am a tenured professor at the University of Arkansas, and the person who hit me had full coverage. I was at work, so workers’ comp was a potential—[nevertheless] all three of these entities pointed a finger at the other and said ‘this is not our responsibility.’”

Dr. Maxson returned to active practice and teaching in the middle of 2018, and he acknowledged the efficiency of the Arkansas Trauma System—which he helped create in 2009—as a key factor in his recovery. Citing a study published in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons, Dr. Maxson noted that the Arkansas Trauma System saved taxpayers $186 million—a ninefold return on investment from the $20 million the states received annually in public funding.

“We had a 31 percent preventable mortality rate in the state of Arkansas in 2008, and by 2013, we cut that number to 16 percent, and now it’s below 10 percent,” Dr. Maxson said. “But what about the 10 to 1 patients who don’t die—patients, like me, who are discharged from the hospital? What is their outcome? That is the piece we don’t know, and I am happy that this is the direction TQIP and the College are moving toward because this is how we will continue to prove our value.”

TQIP update

Dr. Nathens described the difference between error reduction and quality improvement. “An error is the failure of a planned action or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim. Errors occur as a result of an act. Quality improvement modifies the delivery of health care services to increase the likelihood of desired outcomes,” Dr. Nathens said.

An estimated 2 million Americans have died from trauma-related incidents since 2001, and of the 147,790 such U.S. deaths in 2014, approximately 20 percent may have been preventable if appropriate and timely care had been delivered postinjury, Dr. Nathens said. He noted the great variation in the quality of trauma care and outcomes for injured patients in the U.S.

“In November 2018, we rolled out the TQIP Mortality Reporting System, a web-based portal modeled after the Aviation Safety Response System. We now have 300 preventable deaths in the system,” he said, adding that the system is designed to “use the combined experience of TQIP centers to identify patterns and design interventions to reduce preventable deaths.”

Of the cases logged into the system (all IP addresses anonymous), 60 percent are attributed to human failure. “Simply put, mistakes occur because people don’t know what to do because they haven’t been taught or they haven’t learned the information. In these situations, training and education may be effective, but training doesn’t make us any less likely to slip up,” he said. “Slips are the domains of experts—they know what they need to be doing, but due to fatigue or memory lapse, for example, errors can occur.”

Dr. Nathens also summarized other TQIP initiatives, including the November 2019 release of the Best Practices Guidelines for Trauma Recognition of Child Abuse, Elder Abuse, and Intimate Partner Violence—a resource for trauma center health professionals to identify, evaluate, manage, document, and report patients who have been abused. (The guidelines are available for download at facs.org/tqipbestpractices) Quality and process measures also are addressed with specific recommendations for each type of abuse.

Dr. Nathens outlined the new TQIP Data Quality Report, which includes filters such as injury severity, outcomes, and patient characteristics. When a facility receives this report, they are asked to “identify the root causes of the data quality concern, correct and resubmit the data, complete the questionnaire and highlight actions taken, and provide feedback on the overall process.”

The ACS COT has introduced an Advancing Leadership in Trauma Center Management Course—a new two-day, in-person course designed for multidisciplinary participation, Dr. Nathens announced. The course provides strategies for the oversight of trauma system development, performance improvement, effective response models, and high-performance teams. The next course will take place May 14−15 in Chicago, IL.

In addition, Dr. Nathens revealed plans for revising the Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient manual (the Orange Book), including a change in format that will more closely align the book with the other quality programs’ standards. “We are going to align with the new ACS format, and the content will be divided into nine categories, including institutional administrative commitment, program scope and governance, facilities and equipment resources, personnel and services resources, patient care expectations and protocols, data surveillance and systems, quality improvement, professional and community education, and research,” he said.

Dr. Nathens described the standards revision as an “inclusive process with 2,157 responses across [the 23 Orange Book] chapters,” with the goal of developing standards that “ensure utility, relevance, and effectiveness” in providing care for the injured patient. Once the standards revision is completed in the first quarter of 2020, it is anticipated the updated manual will be completed in 2020, with release of the new book in 2021. “We are working to make the transition as smooth as possible for our trauma centers,” Dr. Nathens said.

COT update

ACS COT Chair Eileen M. Bulger, MD, FACS, highlighted several key COT initiatives, most notably in the areas of firearm injury prevention, trauma system development, and Stop the Bleed®.

She summarized the work of the inaugural Medical Summit on Firearm Injury Prevention in February 2019, which brought together representatives from 45 professional medical and injury prevention organizations and the American Bar Association under the leadership of the ACS COT to develop a consensus-based approach to this public health issue. “The meeting was energizing and gave us the opportunity to see where we can better collaborate,” she said.

Dr. Bulger also provided updates on three ACS-led firearm injury prevention initiatives, including the ACS COT Injury Prevention Committee workgroups that are developing best practices in firearm injury prevention along with input from summit partners; the FAST Work Group (Firearm Strategy Team), which consists of surgeons who own firearms and are implementing their recommendations on injury prevention, firearm safety, and advocacy-related activities; and ISAVE (Improving Social Determinants to Attenuate Violence), a multidisciplinary panel of both medical and nonmedical professionals charged with studying the root causes of violence and recommending innovative programs to reduce it.

“We have five stories written for the public on our website describing why having a trauma system is important,” Dr. Bulger said. The series of stories is titled “Putting the Pieces Together: A National Effort to Complete the U.S. Trauma System.”

Dr. Bulger underscored the importance of supporting a national U.S. trauma system. “We have five stories written for the public on our website describing why having a trauma system is important,” she said. The series of stories, titled “Putting the Pieces Together: A National Effort to Complete the U.S. Trauma System,” examines the history of trauma care and trauma system development in America, explores civilian-military partnerships to translate battlefield lessons to the home front and back again, identifies why the 60-year military-civilian partnership is a model for a national trauma system, summarizes the challenges facing America’s trauma systems, and outlines the steps experts are taking to fill the gaps in state and regional systems and achieve the goal of zero preventable deaths and disability from injury.

“Now in its third year, the Stop the Bleed program has trained more than 1.2 million people in all 50 states and in more than 110 countries,” Dr. Bulger noted. “It is on the backs of all of you that we are doing this.” She noted the October 2019 launch of the new public-facing website, stopthebleed.org, which was developed to meet the evolving needs of the general public in terms of education and empowerment. Dr. Bulger also highlighted expanded Stop the Bleed educational offerings in development, including an electronic hybrid course and new versions tailored to specific age groups.

The COT’s 100th anniversary is in 2022, and the committee is looking for feedback on how to mark this milestone, Dr. Bulger added.

Applying high-reliability concepts in trauma

In a session titled High Reliability Concepts Applied to Trauma, speakers defined the characteristics of high-reliability organizations (HROs)—groups connected through a singular function that have the potential for catastrophic failure (firefighters, law enforcement, and so on), yet routinely engage in near error-free performance. “Multiple and unexpected failures are built into society’s complex and tightly coupled systems,” said session moderator, Anne Rizzo, MD, FACS, vice-chair of surgery, Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, VA, noting that operator error is a common issue, much more than issues related to technology.

“HROs are characterized by a preoccupation with failure,” said Chapy Venkatesan, MD, MS, FACP, chief quality and safety officer, Inova Health System. They have “someone who relentlessly looks for any signal of failure, views failure as a symptom of system dysfunction until proven otherwise, doesn’t dwell on success, views failure as an opportunity for learning, and believes that in order to increase your success rate, you have to double your failure rate,” he added.

Integrating a preoccupation with failure into clinical practice requires a “chronic, proactive wariness of the unexpected” and the ability to “recognize something is going wrong before it has gone wrong,” Dr. Venkatesan said. Organizational tactics that promote a preoccupation with failure include simulation training, daily safety briefings, patient safety walk rounds, team-based training, and good/great-catch programs.

Another characteristic of HROs is deference to expertise, noted Charles E. Murphy, MD, CPPS, chief safety officer, Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, who described this concept as situations where “decisions are pushed down into the organization to individuals with expertise and specific knowledge.” Dr. Murphy said cultivating a deference to expertise requires sustaining a “pattern of respectful yielding to those with domain-specific knowledge.”

“Operationalizing deference to expertise relies on the following components: flexible decision structures, support for imagination as a tool for managing the unexpected, an awareness of the fallacy of centrality, and listening with humility,” Dr. Murphy said.

A “reluctance to simplify” is another HRO concept that can be applied to trauma care, according to Paula Graling, DNP, RN, CNOR, FAAN, assistant vice-president, perioperative services, Inova Fairfax Hospital. HROs take “deliberate steps to question assumptions and received wisdom to create a more complete and nuanced picture of ongoing operations.”

“From a trauma perspective, a reluctance to simplify means we view the trauma victim as complex, unstable, unpredictable—a unique individual with a unique response to stress. It also means we facilitate the broader awareness of the team through good communication and foster an understanding that superficial similarities may mask deeper differences. Think it through if the resuscitation is not working,” Ms. Graling said.

A reluctance to simplify also involves mindfulness—“actively searching for disconfirming data” and harnessing “the collaborative wisdom of the surgical care team,” she said.

Dr. Rizzo emphasized that trauma care professionals need to develop a sense of situational awareness, particularly to function effectively within a compressed window of time, and when more than one critical outcome must happen simultaneously. According to Dr. Rizzo, situational awareness in the trauma bay mandates attention to detail, boots on the ground involvement, continuous monitoring, and emotional intelligence.

“If you work in trauma care, chances are you are already very resilient,” said Peter Wu, MD, FASA, CHSE, CPPS, director, anesthesia quality and safety, TeamHealth Anesthesiology, Tampa General Hospital, FL. “The hallmark of an HRO is not that it is error-free, but that errors don’t disable it,” he said.

Dr. Wu noted that a “blame culture,” in which errors are attributed to specific individuals or processes, is counter to fostering resiliency largely because “disciplinary action gives a false sense of confidence” that the error will not be repeated and hampers “transparent reporting and the ability to identify true root causes.”

He encouraged attendees to move beyond traditional root cause analysis because it implies a single cause in a complex system and fails to address corrective actions. Dr. Wu suggested transitioning toward the root cause analysis and action (RCA2) model developed by the National Patient Safety Foundation. RCA2 focuses on systems-based enhancement and on activity that improves, measures, and sustains quality improvement processes aimed at preventing harm to patients.

Hospital-based injury prevention

“Ideally, trauma care systems provide a continuum of care, including prevention, prehospital care, acute care, and rehabilitation,” said David B. Hoyt, MD, FACS, ACS Executive Director. “We have lots of evidence that prevention works, whether it’s related to vehicle safety, alcohol control and intervention, or violence reduction,” he said, noting that successful intervention plans start with rigorous collection of reliable data.

Focusing specifically on firearm-related injuries, Dr. Hoyt said an estimated 100 deaths occur each day. “Many factors contribute to this: mental illness, community distress, childhood trauma, and substance abuse.” The ACS has sought to address these causes and effects “with the work being done by the ACS FAST workgroup, the Firearm Safety and Injury Prevention brochure, the 2019 Medical Summit on Firearm Injury Prevention, and other College programs.”

“By definition, firearm-related violence is a public health issue due to the fact that the issue is population-based,” said Rochelle Dicker, MD, FACS, professor of surgery and anesthesia, vice-chair for critical care, chief of surgical critical care, associate trauma director, University of California-Los Angeles David Geffen School of Medicine. “Firearm homicide is the leading cause of death among African Americans 15–34 years old, and the number two cause of death in Latinos in the same age range. The burden of homicides falls disproportionately on young, minority men.”

“We should practice trauma-informed care. This is an approach that integrates knowledge about the effects of and recovery from trauma, minimizes re-victimization, facilitates recovery and empowerment, and ensures physical and emotional safety,” Dr. Dicker said. To underscore the relevance of hospital-based injury prevention programs, she cited a 2016 study published in the Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery that examined 466 clients enrolled in a hospital-based injury prevention program over a 10-year period. The study revealed that the recidivism rate had fallen from a historical control of 8 percent to 4 percent following participation in this program, and that addressing educational needs of the victim is significantly associated with success.

“A public health approach to firearm injury prevention requires both short- and long-term solutions,” said Brendan T. Campbell, MD, MPH, FACS, the Donald W. Hight Endowed Chair in Pediatric Surgery, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford. Dr. Campbell noted that physicians should not “focus on whether or not a patient owns a gun but focus on providing them useful information in the event that they do own guns—make firearm ownership as safe as possible.”

According to Dr. Campbell, one-third of U.S. children reside in a home with at least one firearm, and 7 percent of U.S. children live in homes where at least one gun is stored and unlocked. “Parents have unrealistic perceptions of children’s capabilities and behavioral tendencies about guns,” he said. He called for making “evidence-based prevention part of our practice,” specifically by “teaching the importance of safe storage, screening for suicide and intimate partner violence, and engaging firearm owners in the development of the overall prevention process.”

Deborah A. Kuhls, MD, FACS, FCCM, chief, section of critical care, division of acute care surgery, and program director, surgical critical care fellowship, University of Nevada Las Vegas School of Medicine; and Chair, ACS COT Injury Prevention and Control Committee, described mental illnesses (including psychiatric, mood, and anxiety disorders, as well as alcohol- and drug-related disorders) and their link to unintentional injuries. She underscored the importance of determining suicide risk in trauma patients using a universal screening tool, such as the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale. She also suggested screening trauma patients for depression using the nine-question Injured Trauma Survivor Screen, which helps predict those most at risk for post-traumatic stress disorder and/or depression six months after admission to a Level I trauma center. She cited a study of 1,048 seriously injured trauma patients in which 60 percent were found to be depressed at discharge, and 31 percent were suffering from depression at the six-month follow-up.

Dr. Kuhls also described the role of the trauma care team in identifying intimate partner violence (IPV), “a silent epidemic that occurs in 4–6 million relationships in the U.S. each year.” She cited the ACS IPV Toolkit as a notable resource for recognizing the signs of IPV in patients, colleagues, and in yourself. The toolkit is available for download from the ACS website.

The 11th annual TQIP Scientific and Meeting and Training will take place December 6–8 at the Phoenix Convention Center, AZ.