What Was Done?

Global Problem Addressed

Acute appendicitis is the most common surgical indication in the pediatric population, yet there remains wide variability in its perioperative management.1 Analysis of such variations in surgical management has introduced opportunities for quality improvement through standardization of care. Numerous studies have shown initiation of standardized protocols has led to more efficient resource utilization and decreased in-hospital costs, and compared with traditional practices, use of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) has been shown to reduce recovery time by as much as 30 percent.2, 3

Although enhanced recovery after surgery has been well-published in the adult literature, multidisciplinary fast-track protocols in pediatric surgery have been slow to generate the same enthusiasm. Recently, studies have demonstrated the feasibility of same day discharge ( <24 hours) following laparoscopic appendectomy in children with non-complicated appendicitis.4-7 However, few pediatric studies have utilized a standardized protocol that is comprehensive and adopts components from ERAS bundle described in the adult population.8

This quality improvement initiative developed an enhanced recovery protocol for non-complicated pediatric appendicitis that was comprehensive (preoperative, intraoperative, postoperative) and took advantage of a dedicated recovery unit. Our goal was to provide a framework for implementation of a multidisciplinary standardized pathway.

Identification of Local Problem

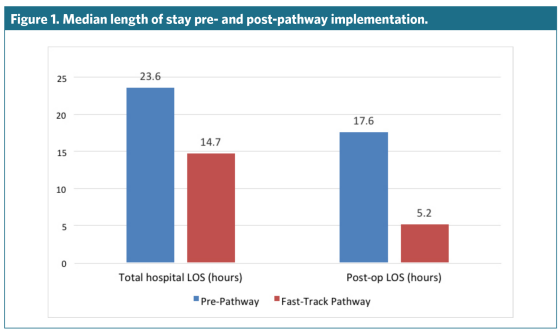

Prior to implementation of our quality improvement initiative, there was no standardized perioperative management for appendicitis at our institution, leading to a wide range of hospital and postop length of stay (LOS). Preoperative antibiotics were based on provider preference while postoperative pain regimens, time to mobilization, and initiation of enteral nutrition were widely nurse driven. Beginning with a common pediatric surgical diagnosis, our goal was to create a standardized perioperative pathway that would reduce interprovider variability, increase compliance with high-quality and evidence-based practices, and ultimately reduce patients' length of stay.

How Was the Quality Improvement (QI) Activity Put in Place?

Context of the QI Activity

Levine Children's Hospital (LCH) is a 235-bed children's hospital in Charlotte, NC, that is affiliated with Atrium Health. As the largest pediatric hospital between Washington and Atlanta and the only pediatric Level 1 trauma center in the region, it serves as the tertiary referral center for pediatric care in North Carolina. In 2017, more than 14,000 perioperative cases were performed. LCH participates in ACS NSQIP Pediatric.

Recent emphasis has been placed on the delivery of value-based care through quality improvement initiatives. At our institution, adult ERAS protocols have been implemented in the divisions of colorectal and HPB surgery, among others, serving as motivation to providers to initiate a similar protocol in the pediatric patient population. In an effort to respond to changing health care needs, we adopted the first pediatric surgery fast-track pathway at Levine Children's Hospital and introduced a multidisciplinary bundle of initiatives to streamline and standardize high-quality surgical care.

Planning and Development Process

A multidisciplinary team of physicians and nurses was formed, including members of the divisions of pediatric surgery, perioperative nursing, anesthesia, and emergency medicine. During initial planning meetings, team members identified potential areas for intervention based on evidence-based practices as well as perceived barriers to discharge. Current guidelines, such as those for antibiotic regimen, were also used during the planning process. A standard fast track pathway for non-complicated appendicitis was created with initiatives to standardize care in each perioperative phase, from diagnosis to discharge. The effectiveness and feasibility of implementing each initiative was discussed by the multidisciplinary team prior to reaching a consensus on fast-track pathway components. A preexisting physical unit adjacent to the operating room was newly designated as the dedicated preop and postop recovery unit. Additionally, the initial driver of culture change and nursing leadership to implement the pathway was under the direction of a single clinical nursing educator, who was critical during the planning process.