What Was Done?

Global Problem Addressed

The population is aging, and while care for chronic medical conditions has improved, optimization for surgical procedures is a complicated process. Medical and surgical complications continue to threaten the elderly and those with complicating comorbid conditions.1,2 Connecticut has some of the highest hospital complication rates and serious safety event rates nationwide. Multiple efforts to improve these outcomes have been condensed into the constellation of “enhanced recovery” processes to optimize patients and improve outcomes after surgery. These programs vary location to location, but overall have made a significant impact in the readiness for surgery, expectation management for patients and families, and an improvement in the overall surgical patient experience. Improved and innovative surgical and anesthetic techniques have contributed to improvements, but low-cost, high-impact efforts like an enhanced recovery program, can make all the difference.

Using a variety of methods and risk assessments, frailty has been demonstrated in between 4.1 and 50.3 percent of surgical patients and is predictive of mortality, postoperative complications, and disposition at discharge.3,4 Complications after surgery are costly—they can increase a case-mix-adjusted costs by $9419 to $13,832 per case.5 More notably, complications worsen patient experience, are concerns to regulatory bodies, and can contribute to higher utilization of health care resources. Enhanced recovery programs (ERP) are being used nationwide and improve complications, reduce lengths of stay, and lower costs of care per patient.6-8 It is widely accepted that no single implemented change will improve outcomes of surgery across all patient populations, and that the approach to perioperative and postoperative care must incorporate multiple disciplines, multiple modalities, and multiple components to optimize care for every patient.

Identification of Local Problem

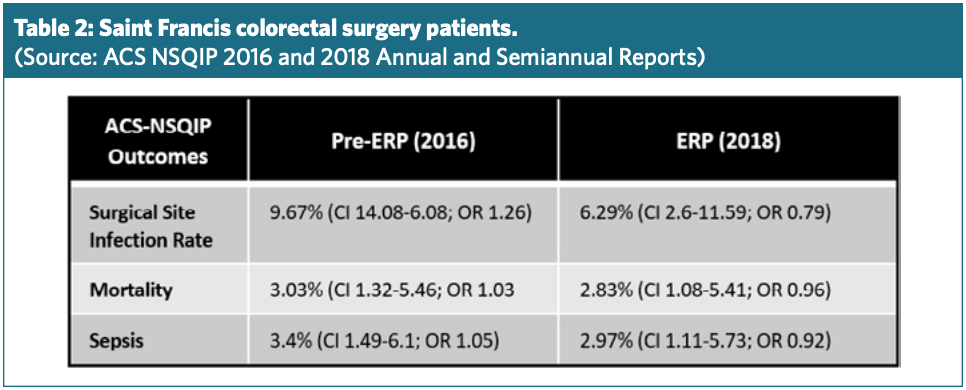

Complications documented by local data assessments, the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN), and the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP®) data identified our hospital as an outlier with respect to overall morbidity, increased lengths of stay, postoperative surgical site infection, sepsis (Source: ACS NSQIP Semiannual Report) as well as transfer to extended care facilities in the post-acute setting, hospital-acquired infections, and postoperative opiate use (Source: NHSN, local data). All listed complications were important to patient experience—events like ileus, reinsertion of a nasogastric tube, and other data not publicly reported.

Our goal was not only to improve care at our campus and within our regional health system, but to disseminate what we have learned locally and from our peer hospitals in the state, and to help to reduce variation and hospital-acquired conditions statewide. Support for the Connecticut Surgical Quality Collaborative has developed a collaborative relationship, where grant funding has provided technology and education statewide, allowing for data collection to be uniform and for techniques to evolve toward being more unified with the best practices demonstrated in the published evidence. This collaboration has borne fruit, with creation of a resource website, the Connecticut Geriatric Program in Surgery (ctgps.org), and a sharing of data to improve care regionally. Lastly, we are not so arrogant as to not recognize our own shortcomings; we have identified several opportunities for systemic improvements through this program and are on the journey toward consistent practice, high reliability, and the safest, most effective surgical providers in the nation.

Saint Francis Hospital, now a part of Trinity Health of New England, has evolved a constellation of practices to reduce hospital-acquired infections (HAI) and conditions over the last several years. As early adopters of large-volume, risk- adjusted surgical data subscriptions, like ACS NSQIP, we have improved multiple metrics across the continuum of care. We have reduced ventilator-associated events, reduced surgical site infections, and adopted enhanced recovery processes (ERP) in our colorectal surgery patients to improve every aspect of their experience. These processes have now begun for patients undergoing hysterectomy and other procedures, and other programs in Connecticut have had success. This project began with pilot data on the implementation of team-based training, best practice utilization, and the idea that state programs would benefit from transparent data sharing. A grant was sought and awarded, and we began our leadership and collaboration with the Connecticut Surgical Safety Collaborative, a partner to the ACS Connecticut Chapter. With a goal of enhancing the patient experience, providing low-cost care, and minimizing complications, we were set to lead the journey toward zero harm.