A commitment to alleviating suffering, improving health, and advocating for the disenfranchised are core tenets of medical practice. These principles apply to individual patients and communities in the US, as well as those around the globe.

Much of the world’s burden of disease is borne by those in economically disadvantaged countries. The highest incidence of infectious diseases, such as malaria and HIV, occurs in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) throughout South America, Africa, and Asia.1 While much funding has historically been allocated to combat communicable diseases, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), including traumatic injury and cancer, continue to increase in LMICs.2

NCDs require healthcare systems with a higher level of complexity and availability of specialists. With the evolution of global health as a field of academic study, there is a growing focus on capacity building through longitudinal partnerships between institutions in high-income countries (HICs) and institutions in LMICs focused on education, clinical care, and research. These partnerships are increasingly important, as federal funding for global health programs has been significantly reduced in recent years, particularly in 2025.

International clinical training remains largely unidirectional, with learners from HICs benefitting from these experiences without reciprocity for trainees and faculty from LMICs.3 This educational inequity stems from prohibitions restricting participation in clinical care for international medical graduates (IMGs) outside of an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education-approved training program. Hence, short-term medical education programs (MEPs) that include clinical care, even if supervised, are not permissible for IMG trainees or faculty. Rather, these individuals are restricted to observerships and simulation, which offer limited educational value, particularly for procedure-based specialties. The US is unique in these restrictions, with peer countries such as Canada and the UK freely allowing IMGs to participate in short- or long-term clinical MEPs that are not part of a formal training program.

Bidirectional Education Sustains Global Workforce

These unidirectional partnerships with LMIC institutions create an imbalance of opportunity and limit the potential of global health system strengthening and security. Without the opportunity to engage in hands-on clinical care in the US, many IMGs turn to other countries that offer this training, thus undermining American diplomatic and academic relationships.

In turn, US training programs lose the opportunity to host, learn from, and exchange clinical skills with world-class talent. As a global leader in healthcare, peace, and security, the US is in a strong position to strengthen bidirectional healthcare education and promote healthcare diplomacy.

As federal funding for global programs is reduced, bidirectional education MEPs are one strategy to maintain engagement in building a strong healthcare workforce worldwide. Furthermore, such programs promote equity in medical education opportunities, facilitate partnerships, drive innovation, and promote global health stability. Additionally, bidirectional MEPs will allow the US to fulfill its security objectives to bolster interoperability with military partners and allied nations.

True bidirectional MEPs offer multiple benefits to IMGs and US-based institutions.

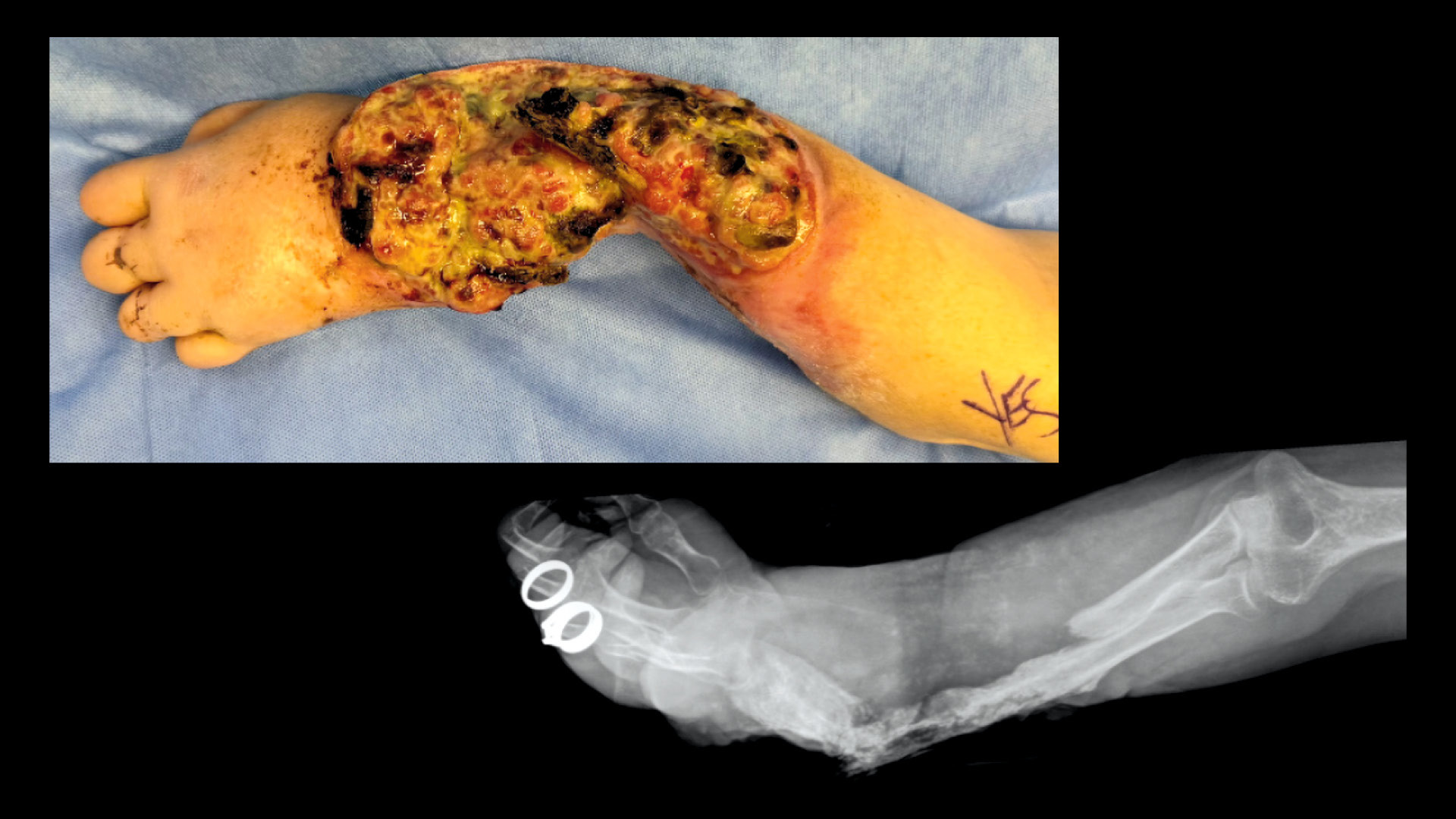

Benefits to IMGs: The US has one of the premier medical education systems in the world and offers one of the highest levels of medical care. Opportunities to spend short periods of time training alongside US physicians allow for expertise and skill transfer. Systems-based learning on how to run a Level I trauma center or establish a multidisciplinary cancer center is most effectively accomplished by seeing one in action. Only a few such centers exist in LMICs, so experience in an HIC is one of the only ways to acquire these specialized skills. Exposure to different medical paradigms fosters creativity and collaboration in addressing local health challenges.

Benefits to the US: IMGs from LMICs bring unique perspectives on providing high-quality healthcare when resources are constrained. These individuals offer creative solutions and novel approaches that are sometimes adopted in the US. The current technique for temporary abdominal closure for severe abdominal injuries in the US is known as the “Bogota bag,” named after the city in which it was pioneered.

Building capability for healthcare in LMICs means a higher level of care when medical issues arise for US citizens abroad.

Barriers to Establishing MEPs

Currently, no pathway exists for establishing equitable MEPs because of three barriers.4

Institutional: Potential host institutions in the US cite concerns about the adequacy of supervision, obtaining malpractice coverage, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliance, and potential risk to patients.

Licensing: State medical licenses and license exemptions are the responsibility of individual state medical boards. Equitable, bidirectional clinical MEPS would allow IMGs who are short-term clinical visitors to “practice medicine.” While the precise definition of what that includes is defined by individual boards, it generally means to “engage, with or without compensation, in medical diagnosis, healing, treatment or surgery.”5

While state boards are generally supportive of opportunities for bidirectional exchange, there is tremendous variation in licensure categories that could unintentionally act as barriers for a short-term, supervised MEP.

Federal Visas: Current visas for nonimmigrant medical trainees require multiple steps, including passing Steps 1 and 2 of the US Medical Licensing Examination, passing an English language proficiency test, obtaining certification by the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates, and being accepted into an approved residency/fellowship program. Aside from the time (1–3 years) and cost ($5,000) required to navigate this process, the effort is hardly worth it for a short-term clinical rotation in the US. None of the existing visas allow for a short-term rotation that would include patient contact.

Potential Solutions for Attaining Reciprocal Training

Achieving bidirectionality in global MEP requires changes at state and federal levels. Several state medical boards have already created temporary licenses or exemptions for IMGs participating in a short-term clinical MEP, with other states considering such amendments.6 These licenses cannot be used without a visa to legally enter the US.

The Building Reciprocal Initiatives for Global Healthcare Training (B.R.I.G.H.T.) coalition was established by key stakeholders to enhance global health education by fostering reciprocal training programs between HICs and LMICs and addressing policy barriers that prohibit short-term clinical MEPs for IMGs. Current work addressing the visa barrier centers around efforts to collaborate with Congress in order to determine and establish an appropriate pathway for IMGs to participate in a short-term clinical MEP.

It is important to note that these efforts to create opportunities for short-term (<12 months) MEP for IMGs in partnership with US-based academic institutions are distinctly different from other efforts to facilitate IMG immigration to the US, which seek to provide a solution to the US physician shortage or address the maldistribution of physicians in rural and socioeconomically disadvantaged communities within our country.7

In contrast, short-term clinical MEPs are partnerships between institutions in LMICs and HICs with the intent of building capacity in the LMIC by enhancing the skill and expertise of the LMIC provider, who will then return to their home country and continue building a stronger healthcare system.

The US, along with other countries around the world, would benefit greatly by developing a critically needed pathway for bidirectional global academic, research, and clinical partnerships.