Biomedical and clinical advances are offering surgeons unprecedented opportunities to provide high-quality functional and aesthetically pleasing outcomes for patients with severe injuries. There are limits, however, to what can be achieved with a purely reconstructive approach.

For individuals who have suffered high-grade facial injuries or disfigurement, lost a major part of their face, and experience extreme functional limitations, an option that is increasingly becoming feasible is facial transplantation.

Surgeons have been slowly but steadily amassing experience and outcomes data on face transplants—once a procedure that seemed more science fiction than clinical reality—since the first successful operation took place in 2005.

Although only 54 face transplants have been completed around the world over the past 20 years, the results of these limited cases have been largely positive. Patients are regaining functionality of their damaged facial subunits, with some limitations, and aesthetic outcomes are constantly improving.1,2

Because of the small number of completed facial transplants, each case represents a significant learning opportunity for surgeons and the transplant care team.

Broad Spectrum of Indications

As with a solid organ transplant, the process of a patient receiving a face transplant is extensive and lengthy, but the unique elements of facial transplant require additional layers of preparation.

A face transplant is a form of vascularized composite allotransplantation (VCA), requiring multiple tissue types including skin, fat, muscle, bone, nerves, and blood vessels.3

As such, “every case is absolutely unique, because the injury and what needs to be replaced is unique,” according to Bruce E. Gelb, MD, FACS, a transplant surgeon and associate professor in the Department of Surgery and Transplant Institute at New York University (NYU) Grossman School of Medicine in New York City, who has served as a medical team leader for NYU Langone’s high-profile face transplants for the last decade.

Due to the limited data points on the technique, however, the indications to pursue a transplant are not firmly set and are up to a surgeon to decide.

“It starts with evaluating the surgical defect, and the team has to agree whether it is something that can be managed conventionally or not,” said Bohdan Pomahac, MD, the Frank F. Kanthak Professor of Surgery (Plastics) and chief of the Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

Dr. Pomahac also led the first face transplant performed in the US in 2011 while he practiced at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts; he has led the most face transplants of any surgeon in the world.

Beyond the surgical and medical indications, equally important are considerations into a patient’s support system, as well as their economic and psychosocial position.

“A face transplant requires that the patient has adequate support. Through a face transplant, we often convert patients who are relatively physically healthy, despite their severe deformity, into somebody who, due to chronic immunosuppression, requires frequent physician visits and follow-ups,” Dr. Pomahac said, which means a significant outlay of time for caregivers and money for copays, transportation, housing, and so on.

All organ transplant recipients work with social workers and psychiatrists to ensure they have the support and cognitive ability to receive the transplant and understand the steps needed to help ensure its function and their health. Face transplant recipients, however, are in the unique position of receiving a transplant with a strong visual component that will influence not only their interactions with the outside world, but also their internal world.

“What I discuss with the patients is that when they come out of surgery, it may rekindle the emotional trauma from their original injury, because they may not be able to see, and they won’t be able to talk or eat at first,” Dr. Gelb said. “They’re going to need to relearn a lot of things during the recovery, and they likely will be in the hospital for a long time.”

Because the transplant recipients will need to be on immunosuppressive medication for the rest of their lives, they cannot opt out of their healthcare. Immunosuppression will almost certainly shorten a recipient’s lifespan and cause medical complications, putting them at risk for diabetes, kidney disease, high blood pressure, and infections.

It is critical that patients understand that a face transplant represents a tradeoff in form and function against overall health. The ongoing logistical and emotional burden of a face transplant requires a strong personal will and commitment to success, as well as long-term mental health support.4

Rigorous Preparations

Once the recipient and care team are in accord on pursuing a face transplant, the significant work of preparing for the complex, lengthy procedure begins in earnest.

“We start by doing rehearsals in the OR on research cadavers. We'll have two rooms, and there'll be two cadaver heads, and one team will be removing the tissue to be transplanted, and the other team will be practicing removing the injured tissue in preparation for transplant,” Dr. Gelb said.

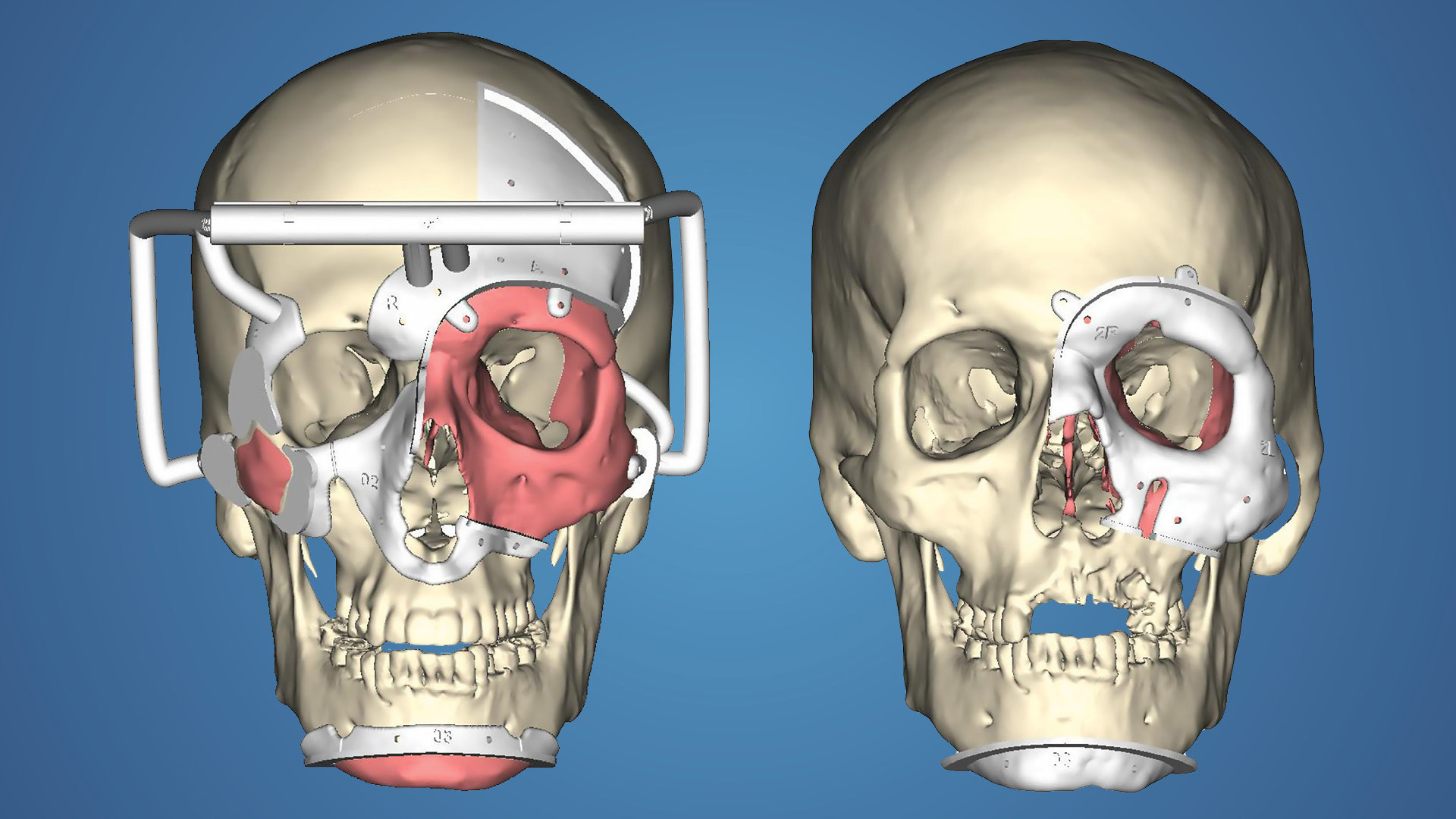

One of the significant developments that has aided in these VCAs is increasingly specific advanced imaging and surgical guides, he added. CT imaging provides clear imaging of the bones, magnetic resonance neurography shows nerves, and venograms, arteriograms, and angiograms highlight vascular system of recipients, allowing surgeons to create a plan showing how the heterogenous tissues will be connected.

After months of preparation and rehearsals based on the recipient’s case profile, once a donor face becomes available, the process accelerates quickly.

“We work up the donor similarly—very rapidly—and then from that, we know we're going to make our bony cuts on both donor and recipient, and we know the vascular anatomy necessary for a successful transplant,” Dr. Gelb said.

But because no two faces are the same and everything must align correctly, part of the computerized surgical plan is creating 3D-printed guides. These are pieces of plastic that snap on so that surgeons know where to make the osteotomies on the donor and recipient.

“The recipient process is completed in advance. On the donor side, we perform the imaging, it gets uploaded, and then the 3D printing starts right away so that we have those cutting guides within a couple hours, and we can proceed with the surgery,” Dr. Gelb said.

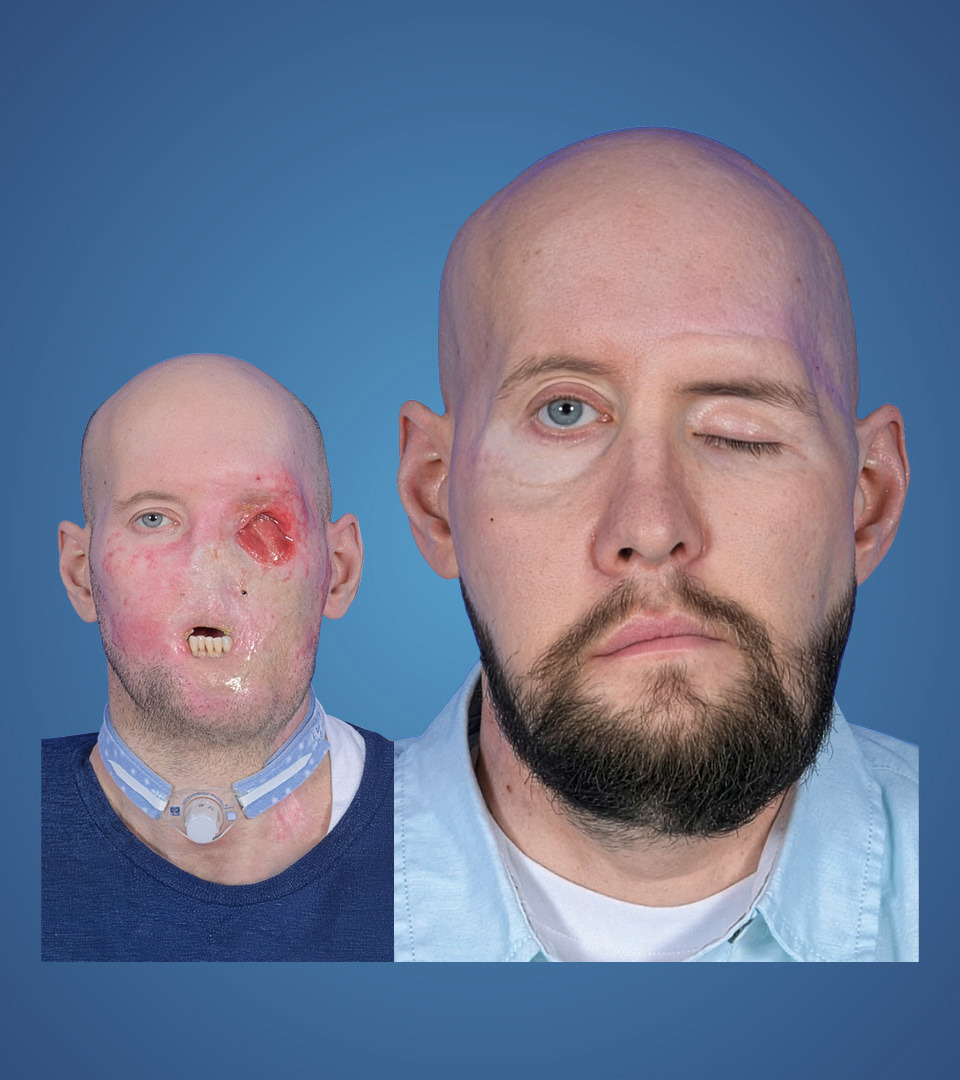

As an example of the utility of presurgical planning, Dr. Gelb described the preparation for a patient who underwent a combined partial-face and whole-eye transplant in May 2023 at NYU Langone.5

The 46-year-old patient experienced a high-voltage burn, where electricity entered the back of his head and conducted through the front. Resultantly, he had severe disfigurement on most of his face and lost his left eye. His mouth was fixed open, so he couldn’t eat or drink and speech was severely affected, and his nose was lost.

There was no conventional reconstruction approach that could come close to what a face transplant offered and, ultimately, achieved, Dr. Gelb said.

Showing how all severe facial injuries, underlying anatomy, and corrective options were unique, it was determined during the planning process that the patient would be best served with a whole-eye transplant—a historic first.

“Because it was an electrical injury that affected deep tissue and bone, we needed to transplant that whole area of the face—but there was a fistula between the eye socket and his nasopharynx. So, we had to fill that space with a transplant, and the only way to do that was to transplant the eye at the same time,” Dr. Gelb said.

“We didn't start off intending to perform an eye transplant, but we had to replace the orbital box, and the safest way to do that is with the eyeball,” he explained.

The patient was on the transplant list for about 4 months before a suitable donor was identified, but Dr. Gelb and the transplant team had started preparing before he was formally placed on the list. At least once a month, the surgical teams performed a rehearsal up until the time they did the transplant, which made for a total of 15 rehearsals over a yearlong period.