Validated Screening Tools for Preoperative Cognitive Impairment

Surgeons may wonder how cognition screening fits into the scope and workflow of their practice and how cognitive impairment may go undiagnosed before the preoperative visit.

It is important to recognize that patients may arrive at the surgical clinic without a prior diagnosis of cognitive impairment or dementia for various reasons. Symptoms of cognitive impairment can be misinterpreted by patients, family members, or primary care physicians as normal processes.

Patients also may delay seeking evaluation or downplay symptoms due to concerns about the associated stigma. When assessing a patient for cognitive impairment symptoms, obtaining input from trusted family members becomes crucial to gain insights into the patient’s daily routine, mood, and behavior over time.

Cognitive impairment in this population can be subtle enough for patients to pass the initial evaluation in the exam room often referred to as the “eyeball test,” which relies solely on clinical observation. Hence, the use of validated screening tools is essential to detect subtle yet clinically significant deficits.

Although cognitive impairment or dementia may be commonly associated with memory decline, it is important to recognize that other cognitive domains, including visuospatial, language, executive function, problem-solving, or social cognition, can only be identified thorough comprehensive cognitive assessment.6

In the preoperative context, there are several validated screening tools available that address multiple cognitive domains. These tools are convenient for surgeons and their supporting staff because they can be completed in 15 minutes or less. Some of the available validated tools include:

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a widely used tool to assess cognitive function. It evaluates various cognitive domains, including short-term memory, visuospatial ability, executive function, attention, language, and orientation. The MoCA can be completed in approximately 10 minutes and is available in paper, digital, or telephone formats.7

- Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) is another frequently used cognitive screening tool that assesses orientation, memory, attention, language, and executive function. The MMSE can be administered in approximately 5 minutes.8

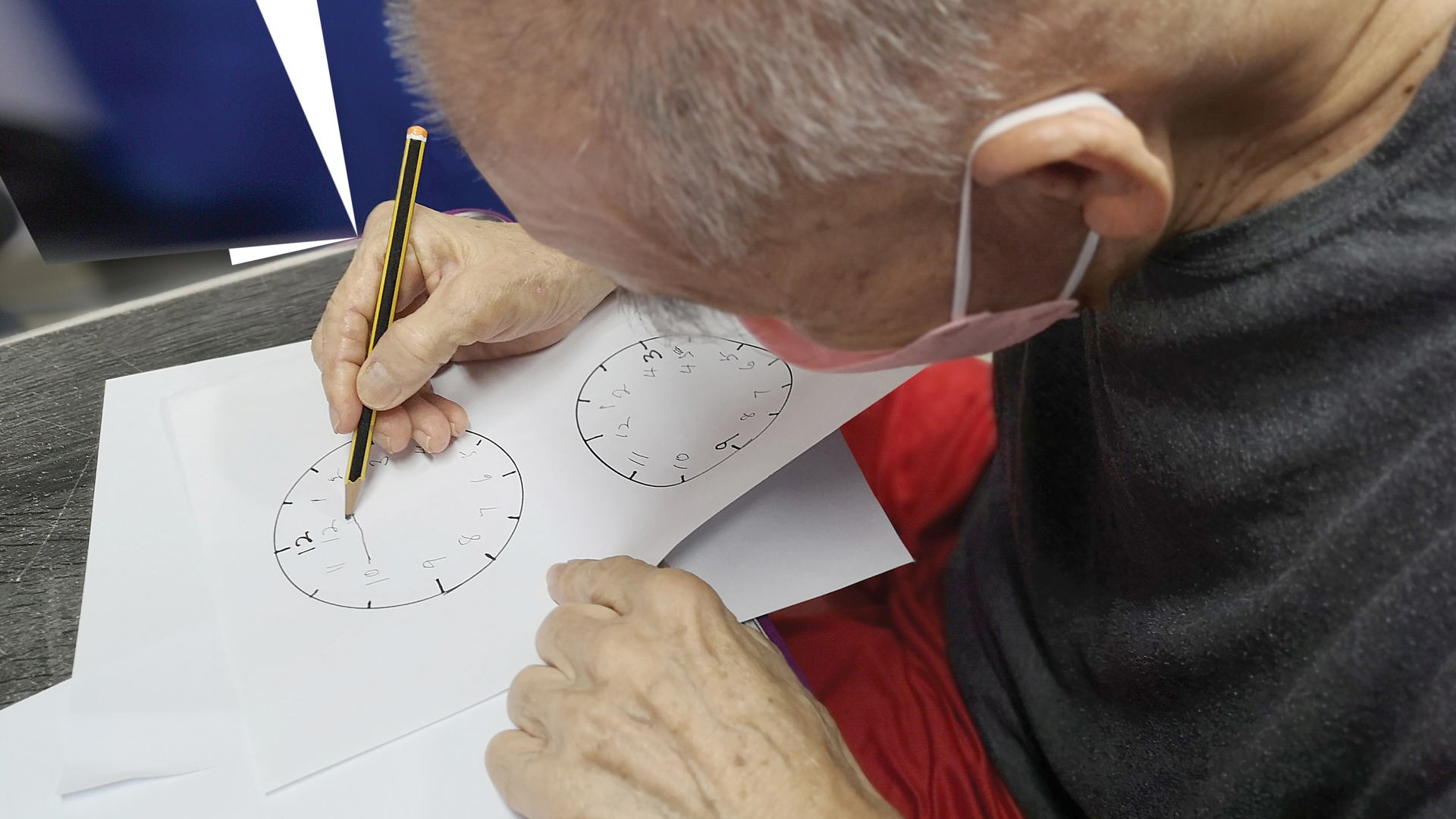

- Mini-Cog is a brief cognitive screening tool that involves a three-word recall task and a clock-drawing test that evaluates visuospatial ability. It can be administered in under 5 minutes, making it a time-efficient option to assess cognitive function.9

- Saint Louis University Mental Status is another cognitive screening tool that is readily available and can be administered in fewer than 10 minutes.10

Although each screening tool has its own strengths and weaknesses, they all share the advantage of requiring minimal time investment while providing substantial benefits to patients, families, and care teams. However, it is important to acknowledge that patients may exhibit variable performance on these screening tests due to differences in their cultural, linguistic, and educational backgrounds.

Implementation of a screening process requires thoughtful evaluation of available resources and careful consideration of how it can be seamlessly integrated into regular preoperative surgical practice. This integration may be achieved through the administration of a preoperative screening test in the clinic waiting room by clinic support personnel. Participation in the ACS Geriatric Surgery Verification Program provides a practice-based approach to successfully integrate cognitive screening instruments, mitigate risks, and enhance the decision-making process in the care of older surgical patients.

What Can I Do If a Patient Screens Positive?

As a surgeon, there are several steps you can take when a patient screens positive for preoperative cognitive impairment:

Communicate Effectively

Adapt your communication style to accommodate the patient’s cognitive impairment. Use clear and simple language, allow extra time for comprehension, and consider providing visual aids like pictures or videos. Encourage questions from the patient and their family members.

Involve the Patient’s Support System

Engage family members or caregiver(s) in the decision-making process and ensure they are well-informed about the patient’s condition. These individuals can provide valuable insights and assistance in managing the patient’s care. Consider providing additional resources and shifting responsibilities to family and other support mechanisms.

Risk Assessment and Goals-of-Care Discussion

Just like you discuss increased risk of perioperative cardiac events for patients with underlying cardiac disease, talk about increased risk of delirium, related consequences (e.g., loss of function), and other adverse postoperative outcomes associated with cognitive impairment.

Discuss the patient’s treatment preferences and potential risks to ensure the expected outcomes of surgical intervention match your patient’s health-related goals and quality-of-life objectives. Allocate extra time and resources for in-depth discussions to facilitate informed and meaningful decision-making regarding the necessity, potential benefits, and risks of the proposed operation.

Additionally, explore alternative pathways and treatment options, considering the individual circumstances and preferences of each patient. Established values and preferences documented before surgery can serve as a valuable reference and can guide future decision-making processes in the event that a patient develops postoperative delirium and/or loses the capacity to make decisions.

Collaborate with Other Healthcare Professionals

Consult with geriatricians, neurologists, or other specialists experienced in managing cognitive impairment. Involve a case manager and social worker teams if needed. Their expertise can help guide the perioperative care plan and address specific needs or concerns.

Optimize Perioperative Care

- Counsel patients and families on their critical roles in prevention, identification, and management of postoperative delirium.

- Activate and inform perioperative care teams to implement evidence-based delirium prevention strategies to minimize the occurrence of postoperative delirium and the associated deleterious outcomes. This approach may include appropriate medication management, maintaining a familiar environment, frequent reorientation, maintenance of normal sleep wake cycles, opioid-sparing multimodal pain regimens, regular mobilization, and immediate return of sensory aids postoperatively.

- Inform anesthesiology team members to avoid agents with high anticholinergic burden during surgery and minimize opioids in the perioperative recovery care unit.

- Provide instructions to surgical recovery team members about placing patients with preoperative cognitive impairment near windows and involving family members immediately after surgery to help with efficient orientation and maintenance of normal sleep wake cycles.

- Review all home medications and decrease anticholinergic burden through dose adjustment or deprescribing with expert input.

Coordinate Postoperative Care and Support

Collaborate with the healthcare team to ensure a smooth transition from the hospital to postoperative settings. Provide appropriate referrals for rehabilitation, social workers, home care, or cognitive support services as needed.

Follow Up and Monitor

Schedule regular follow up appointments to assess the patient’s recovery and cognitive function. Monitor for any changes or complications that may require further intervention.

It is important to note that formal diagnosis for cognitive impairment is established through rigorous testing, including patient interviews and questionnaires, neurological examination, and neuropsychological tests—all of which lie outside the time constraints and clinical scope of a practicing surgeon. Patients with positive screens for cognitive impairment should follow-up with a geriatrician or neurologist in addition to the action items listed here.

By taking these proactive measures, surgeons can optimize care and outcomes for patients who screened positive for cognitive impairment.

Preoperative cognitive screening is a crucial component of preoperative assessment in older surgical adults, similar to preoperative cardiac and pulmonary assessments.

The presence of cognitive impairment prior to surgery significantly increases the risk of undesirable postoperative outcomes and impacts patients’ ability to participate in their surgical decision-making and perioperative care, necessitating careful considerations for perioperative care. Therefore, preoperative cognitive screening is essential to identify patients at high risk for adverse postoperative outcomes and those who require more comprehensive care planning, additional resources, and thoughtful discussions about the goals of care throughout both preoperative and postoperative periods.

By identifying patients with preoperative cognitive impairment, surgery team members can implement strategies to prevent adverse outcomes associated with cognitive impairment in the surgical setting. This proactive approach enables care teams to plan for a successful recovery and ensure a safe transition of care. Overall, preoperative cognitive screening empowers the care team to take appropriate measures to optimize outcomes and provide comprehensive care tailored to the specific needs of older surgical adults with cognitive impairment.

For more information, listen to episode 18 of the House of Surgery podcast series, “Cognitive Impairment Screening,” hosted by Dr. Xane Peters, at facs.org/houseofsurgery.